Chaco Culture National Historical Park

| Chaco Culture National Historical Park | |

The Great Kiva of Chetro Ketl

|

|

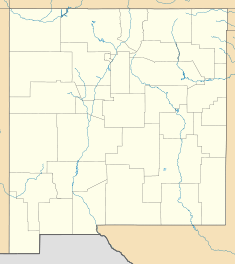

| Location: | San Juan County and McKinley County, New Mexico, USA |

| Coordinates: | |

| Area: | 33,977.8 acres (13,750.3 ha) |

| Visitation: | 45,539 (2005) |

| Governing body: | National Park Service |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name: Chaco Culture | |

| Type: | Cultural |

| Criteria: | iii |

| Designated: | 1987 (11th session) |

| Reference #: | 353 |

| State Party: | |

| Region: | Europe and North America |

| U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

| Type: | U.S. historic district |

| Designated: | October 15, 1966 |

| Reference #: | 66000895[1] |

| Former U.S. National Monument | |

| Designated: | March 11, 1907 |

| Delisted: | December 19, 1980 |

| Designated by: | President Theodore Roosevelt |

| U.S. National Historical Park | |

| Designated: | December 19, 1980 |

Location of Chaco Culture National Historical Park in New Mexico

|

|

Chaco Culture National Historical Park is a United States national historical park hosting the densest and most exceptional concentration of pueblos in the American Southwest. The park is located in northwestern New Mexico, between Albuquerque and Farmington, in a remote canyon cut by the Chaco Wash. Containing the most sweeping collection of ancient ruins north of Mexico, the park preserves the United States' most important precolumbian cultural and historic area.[2]

Between AD 900 and 1150, Chaco Canyon was a major center of culture for the Ancient Pueblo Peoples.α[›] Chacoans quarried sandstone blocks and hauled timber from great distances, assembling 15 major complexes which remained the largest buildings in North America until the 19th century.[2][3] Evidence of archaeoastronomy at Chaco has been proposed, with the Sun Dagger petroglyph at Fajada Butte a popular example. Many Chacoan buildings may have been aligned to capture the solar and lunar cycles,[4] requiring generations of astronomical observations and centuries of skillfully coordinated construction.[5] Climate change is thought to have led to the emigration of Chacoans and the eventual abandonment of the canyon, beginning with a 50-year drought in 1130.[6]

Composing a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in the arid and sparsely populated Four Corners region, the Chacoan cultural sites are fragile; fears of erosion caused by tourists have led to the closure of Fajada Butte to the public. The sites are considered sacred ancestral homelands by the Hopi and Pueblo people, who maintain oral accounts of their historical migration from Chaco and their spiritual relationship to the land.[7][8] Though park preservation efforts can conflict with native religious beliefs, tribal representatives work closely with the National Park Service to share their knowledge and respect the heritage of the Chacoan culture.[7]

Contents |

Geography

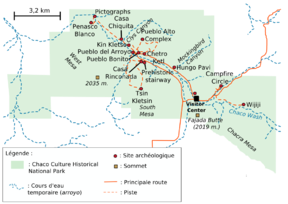

Chaco Canyon lies within the San Juan Basin, atop the vast Colorado Plateau, surrounded by the Chuska Mountains in the west, the San Juan Mountains to the north, and the San Pedro Mountains in the east. Ancient Chacoans drew upon dense forests of oak, piñon, ponderosa pine, and juniper to obtain timber and other resources. The canyon itself, located within lowlands circumscribed by dune fields, ridges, and mountains, runs in a roughly northwest-to-southeast direction and is rimmed by flat massifs known as mesas. Large gaps between the southwestern cliff faces—side canyons known as rincons—were critical in funneling rain-bearing storms into the canyon and boosting local precipitation levels.[9] The principal Chacoan complexes, such as Pueblo Bonito, Nuevo Alto, and Kin Kletso, have elevations of 6,200 to 6,440 feet (1,890 to 1,960 m).

The alluvial canyon floor slopes downward to the northeast at a gentle grade of 30 feet (9.1 m) per mile (6 meters per kilometer); it is bisected by the Chaco Wash, an arroyo that rarely bears water. Of the canyon's aquifers, the largest are located at a depth that precluded ancient Chacoans from drawing groundwater: only several smaller, shallower sources supported the small springs that sustained them.[10] Aside from occasional storm runoff coursing through arroyos, significant surface water is virtually non-existent.

Geology

After the Pangaean supercontinent sundered during the Cretaceous period, the region became part of a shifting transition zone between a shallow inland sea—the Western Interior Seaway—and a band of plains and low hills to the west. A sandy and swampy coastline oscillated east and west, alternately submerging and uncovering the area atop the present Colorado Plateau that Chaco Canyon now occupies.[11]

As the Chaco Wash flowed across the upper strata of what is now the 400-foot (120 m) Chacra Mesa, it cut into it, gouging out a broad canyon over the course of millions of years. The mesa comprises sandstone and shale formations dating from the Late Cretaceous,[12] which are of the Mesa Verde formation.[11] The canyon bottomlands were further eroded, exposing Menefee Shale bedrock; this was subsequently buried under roughly 125 feet (38 m) of sediment. The canyon and mesa lie within the "Chaco Core", distinct from the wider Chaco Plateau, the latter a flat region of grassland with infrequent stands of trees. Because the Continental Divide is only 15.5 miles (25 km) east of the canyon, geological characteristics and different patterns of drainage differentiate these two regions both from each other and from the nearby Chaco Slope, the Gobernador Slope, and the Chuska Valley.[13]

Climate

An arid region of high xeric scrubland and desert steppe, the canyon and wider basin average 8 inches (200 mm) of rainfall annually; the park averages 9.1 inches (230 mm). Chaco Canyon lies on the leeward side of extensive mountain ranges to the south and west, resulting in a rainshadow effect fostering the prevailing lack of moisture in the region.[14] Four distinct seasons define the region, with rainfall most likely between July and September; May and June are the driest months. Orographic precipitation, resulting from moisture wrung out of storm systems ascending mountain ranges around Chaco Canyon, is responsible for most precipitation in both summer and winter; rainfall increases with higher elevation.[12] Occasional abnormal northward excursions of the intertropical convergence zone may boost precipitation in some years.

Chaco endures remarkable climatic extremes: temperatures range between -38 to 102 °F (-39 to 39 °C),[15] and temperatures may swing 60 °F (33 °C) in one day.[7] The region averages less than 150 frost-free days per year, and the local climate swings wildly from years of plentiful rainfall to prolonged drought.[16] The heavy influence of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation contributes to the canyon's fickle climate.[15]

Flora and fauna

Chacoan flora typifies that of North American high deserts: sagebrush and several species of cactus are interspersed with dry scrub forests of piñon and juniper, the latter primarily on mesa tops. The canyon is far drier than other parts of New Mexico located at similar latitudes and elevations, and it lacks the temperate coniferous forests plentiful to the east. The prevailing sparseness of plants and wildlife was echoed in ancient times, when overpopulation, expanding cultivation, overhunting, habitat destruction, and drought may have led the Chacoans to strip the canyon of wild plants and game.[17] As such, even during wet periods, the canyon was able to sustain only 2,000 people.[18]

The canyon's most notable mammalian species include the ubiquitous coyote (Canis latrans); mule deer, elk, and pronghorn also live within the canyon, though they are rarely encountered by visitors. Important smaller carnivores include the bobcats, badgers, foxes, and two species of skunk. The park hosts abundant populations of rodents, including several prairie dog towns. Small colonies of bats, are present during the summer. The local shortage of water means that relatively few bird species are present; these include roadrunners, large hawks (such as Cooper's Hawks and American Kestrels), owls, vultures, and ravens, though they are less abundant in the canyon than in the wetter mountain ranges to the east. Sizeable populations of smaller birds, including warblers, sparrows, and house finches, are also common. Three species of hummingbirds are present, including the tiny, but highly pugnacious, Rufous Hummingbird; they compete intensely with the more mild-tempered Black-chinned Hummingbirds for breeding habitat in shrubs or trees located near water. Western (prairie) rattlesnakes are occasionally seen in the backcountry, though various lizards and skinks are far more abundant.

History

Ancestral Puebloans

The first people in the San Juan Basin were hunter-gatherers: the Archaic. These small bands descended from nomadic Clovis big-game hunters who arrived in the Southwest around 10,000 BC.[19] By 900 BC, Archaic people lived at Atlatl Cave and like sites.[20] They left little evidence of their presence in Chaco Canyon. By AD 490, their descendants, called the Basketmakers by archaeologists, farmed lands around Shabik'eshchee Village and other pithouse settlements at Chaco.

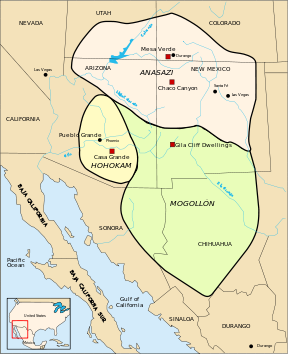

A small population of Basketmakers remained in the Chaco Canyon area. The broad arc of their cultural elaboration culminated around 800, when they were building crescent-shaped stone complexes, each comprising four to five residential suites abutting subterranean kivas,[21] large enclosed areas reserved for rites. Such structures characterize the Early Pueblo People. By 850, the Ancient Pueblo population—the "Anasazi", from a Ute term adopted by the Navajo denoting the "ancient ones" or "enemy ancestors"—had rapidly expanded: groups resided in larger, denser pueblos. Strong evidence attests to a canyon-wide turquoise processing and trading industry dating from the 10th century. Around then, the first section of Pueblo Bonito was built: a curved row of 50 rooms near its present north wall.[22][23]

The cohesive Chacoan system began unravelling around 1140, perhaps triggered by an extreme 50-year drought that began in 1130;[24] chronic climatic instability, including a series of severe droughts, again struck the region between 1250 and 1450.[25] Other factors included water management patterns (leading to arroyo cutting) and deforestation.[26][27][28] For instance, timber for construction was imported from outlying mountain ranges, such as the Chuska Mountains over 50 miles (80 km) to the west.[29] Outlying communities began to disappear and, by the end of the century, the buildings in the central canyon had been carefully sealed and abandoned.

Some scholars suggest that violence and warfare, perhaps involving cannibalism, impelled the evacuations. Hints of such include dismembered bodies—dating from Chacoan times—found at two sites within the central canyon.[30] Yet Chacoan complexes showed little evidence of being defended or defensively sited high on cliff faces or atop mesas, and only several minor sites at Chaco evidence the large-scale burning that would suggest enemy raids.[31] Archaeological and cultural evidence leads scientists to believe people from this region migrated south, east, and west into the valleys and drainages of the Little Colorado River, the Rio Puerco, and the Rio Grande.[32]

Anthropologist Joseph Tainter deals at length with the structure and decline of Chaco civilization in his 1988 study The Collapse of Complex Societies.

Athabaskan succession

Numic-speaking peoples, such as the Ute and Shoshone, were present on the Colorado Plateau beginning in the 12th century. Nomadic Southern Athabaskan speaking peoples, such as the Apache and Navajo, succeeded the Pueblo people in this region by the 15th century; in the process, they acquired Chacoan customs and agricultural skills.[32][33] Ute tribal groups also frequented the region, primarily during hunting and raiding expeditions. The modern Navajo Nation lies west of Chaco Canyon, and many Navajo live in surrounding areas. The arrival of the Spanish in the 17th century inaugurated an era of subjugation and rebellion, with the Chaco Canyon area absorbing Puebloan and Navajo refugees fleeing Spanish rule. In succession, as first Mexico, then the U.S., gained sovereignty over the canyon, military campaigns were launched against the region's remaining inhabitants.[34]

Excavation and protection

![Large square map of northwestern New Mexico and neighboring parts of, clockwise from left, western Arizona, southeastern Utah, and southwestern Colorado. The map region has a green and blocky rectangular-crescent area at its center labeled "Chaco Culture National Historical Park". Radiating from the green region are seven segmented gold lines: "[p]rehistoric roads", each several dozen kilometers in length when measured according to the map scale factor. Roughly seventy red dots mark the location of "Great House[s]"; they are widely spread across the map, many of them far from the green area, near the extremes of the map, more than one hundred kilometers from the green area. Two proceed roughly south, one southwest, one northwest, one straight north, and the last to the southeast. Yellow dots mark the location of modern settlements: "Shiprock", "Cortez", "Farmington", and "Aztec" to the northwest and north; "Nageezi", "Cuba", and "Pueblo Pintado" to the northeast and east; "Grants", "Crownpoint", and "Gallup" to the south and southwest. They are connected by a network of gray lines marking various interstate and state highways. A fan of thin blue lines along the northern margins of the map depict the San Juan River and its communicants.](/I/288px-San_Juan_Basin_Prehistoric_Roads.jpg)

The trader Josiah Gregg was the first to write about the ruins of Chaco Canyon, referring in 1832 to Pueblo Bonito as "built of fine-grit sandstone". In 1849, a U.S. Army detachment passed through and surveyed the ruins.[35] The canyon was so remote, however, that it was scarcely visited over the next 50 years. After brief reconnaissance work by Smithsonian scholars in the 1870s, formal archaeological work began in 1896 when a party from the American Museum of Natural History—the Hyde Exploring Expedition—began excavating Pueblo Bonito. Spending five summers in the region, they sent over 60,000 artifacts back to New York and operated a series of trading posts.[36]

In 1901 Richard Wetherill, who had worked for the Hyde expedition, claimed a homestead of 161 acres (65 ha) that included Pueblo Bonito, Pueblo del Arroyo, and Chetro Ketl.[37][38] While investigating Wetherill's land claim, federal land agent Samuel J. Holsinger detailed the physical setting of the canyon and the sites, noted prehistoric road segments and stairways above Chetro Ketl, and documented prehistoric dams and irrigation systems.[39][40] His report, which went unpublished, urged the creation of a national park to safeguard Chacoan sites. The next year, Edgar Lee Hewett, president of New Mexico Normal University (later renamed New Mexico Highlands University), mapped many Chacoan sites. Hewett and others helped enact the Federal Antiquities Act of 1906, the first U.S. law to protect relics; it was, in effect, a direct consequence of Wetherill's controversial activities at Chaco.[41] The Act also authorized the President to found national monuments: on March 11, 1907, Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed Chaco Canyon National Monument. Wetherill relinquished his claims.[7]

In 1920, the National Geographic Society began an archaeological examination of Chaco Canyon, and appointed Neil Judd, then 32, to head the project. After a reconnaissance trip that year, Judd proposed to excavate Pueblo Bonito, the largest ruin at Chaco. Beginning in 1921, Judd spent seven field seasons at Chaco. Living and working conditions were spartan at best. In his memoirs, Judd noted dryly that "Chaco Canyon has its limitations as a summer resort." By 1925, Judd's excavators had removed 100,000 short tons of overburden, using a team of "35 or more Indians, ten white men, and eight or nine horses." One puzzling discovery was that Judd's team only found 69 hearths in the ruin; winters are cold at Chaco.[42]

Judd sent A. E. Douglass more than 90 specimens for tree-ring dating, then in its infancy. At that time, Douglass had only a "floating" chronology. it was not until 1929 that a Judd-led team found the "missing link." Most of the beams used at Chaco were cut between 1033 and 1092, the height of construction there.[42]

In 1949, the University of New Mexico deeded over adjoining lands to form an expanded Chaco Canyon National Monument. In return, the university maintained scientific research rights to the area. By 1959, the National Park Service had constructed a park visitor center, staff housing, and campgrounds. As a historic property of the National Park Service, the National Monument was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. In 1971, researchers Robert Lister and James Judge established the Chaco Center, a division for cultural research that functioned as a joint project between the University of New Mexico and the National Park Service. A number of multi-disciplinary research projects, archaeological surveys, and limited excavations began during this time. The Chaco Center extensively surveyed the Chacoan roads, well-constructed and heavily built thoroughfares radiating from the central canyon.[43] The results from such research conducted at Pueblo Alto and other sites dramatically altered accepted academic interpretations of both the Chacoan culture and the Four Corners region of the American Southwest.

The richness of the cultural remains at park sites led to the expansion of the small National Monument into the Chaco Culture National Historical Park on December 19, 1980, when an additional 13,000 acres (5,300 ha) were added to the protected area. In 1987, the park was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. To safeguard Chacoan sites on adjacent Bureau of Land Management and Navajo Nation lands, the Park Service developed the multi-agency Chaco Culture Archaeological Protection Site program. These initiatives have detailed the presence of more than 2,400 archeological sites within the current park's boundaries; only a small percentage of these have been excavated.[43][44]

Management

Chaco Culture National Historical Park is managed by the National Park Service, a federal agency within the Department of the Interior; neighboring federal lands hosting Chacoan roads are controlled by the Bureau of Land Management. In the 2002–2003 fiscal year, the park's total annual operating budget was US$1,434,000.[45] The park has a visitor center, which features the Chaco Collection Museum, an information desk, a theater, a book store, and a gift shop.

Prior to the 1980s, archeological excavations within current park boundaries were intensive: compound walls were dismantled or demolished, and thousands of artifacts were extracted. Starting in 1981, a new approach, informed by traditional Hopi and Pueblo beliefs, stopped such intrusions. Remote sensing, anthropological study of Indian oral traditions, and dendrochronology—which left Chacoan relics undisturbed—were touted. In this vein, the Chaco American Indian Consultation Committee was established in 1991 to give Navajo, Hopi, Pueblo, and other Indian representatives a voice in park oversight.[7]

Current park policy mandates partial restoration of excavated sites. "Backfilling", or re-burying excavated sites with sand, is one such means.[7] Other measures attempt to safeguard the area's ancient ambiance and mystique: the Chaco Night Sky Program, which seeks to eliminate the impact of light pollution on the park's acclaimed night skies; under the program, some 14,000 visitors make use of the Chaco Observatory (inaugurated in 1998), park telescopes, and astronomy-related programs.[7] Chacoan relics outside the current park's boundaries have been threatened by development: an example was the proposed competitive leasing of federal lands in the San Juan Basin for coal mining beginning in 1983. As ample coal deposits abut the park, this strip mining threatened the web of ancient Chacoan roads. The year-long Chaco Roads Project thus documented the roads, which were later protected from the proposed mining.[46]

Sites

The Chacoans built their complexes along a nine-mile (14 km) stretch of canyon floor, with the walls of some structures aligned cardinally and others aligned with the 18.6 year cycle of minimum and maximum moonrise and moonset. Nine Great Houses are positioned along the north side of Chaco Wash, at the base of massive sandstone mesas. Other Great Houses are found on mesa tops or in nearby washes and drainage areas. There are 14 recognized Great Houses, which are grouped below according to geographic positioning with respect to the canyon.

Central canyon

The central portion of the canyon contains the largest Chacoan complexes. The most studied is Pueblo Bonito ("Beautiful Village"); covering almost 2 acres (0.81 ha) and comprising at least 650 rooms, it is the largest Great House; in parts of the complex, the structure was four stories high. The builders' use of core-and-veneer architecture and multi-story construction necessitated massive masonry walls up to 3 feet (91 cm) thick. Pueblo Bonito is divided into two sections by a wall precisely aligned to run north-south, bisecting the central plaza. A Great Kiva was placed on either side of the wall, creating a symmetrical pattern common to many Chacoan Great Houses. The scale of the complex, upon completion, rivaled that of the Colosseum.[5]

Nearby is Pueblo del Arroyo. Founded between AD 1050 and 1075, completed in the early 12th century, it sits at a drainage outlet known as South Gap. Casa Rinconada, eloigned from other sites at Chaco. It sits to the south side of Chaco Wash, adjacent to a Chacoan road leading to a set of steep stairs that reached the top of Chacra Mesa. Its sole kiva stands alone, with no residential or support structures whatever; it did once had a 39-foot (12 m) passageway leading from the underground kiva to several above-ground levels. Chetro Ketl, located near Pueblo Bonito, bears the typical D-shape of many other central complexes, but is slightly smaller. Begun between AD 1020 and 1050, its 450–550 rooms shared one Great Kiva. Experts estimate that it took 29,135 man-hours to erect Chetro Ketl alone; Hewett estimated that it took the wood of 5,000 trees and 50 million stone blocks.[47]

Kin Kletso ("Yellow House") was a medium-sized complex located 0.5 miles (800 m) west of Pueblo Bonito. It shows strong evidence of construction and occupation by Pueblo peoples from the northern San Juan Basin. Its rectangular shape and design is related to the Pueblo II cultural group, rather than the Pueblo III style or its Chacoan variant. It contains around 55 rooms, four ground-floor kivas, and a two-story cylindrical tower that may have functioned as a kiva or religious center. Evidence of an obsidian-processing industry was discovered near the village, which was erected between AD 1125 and 1130.[48]

Pueblo Alto, a Great House of 89 rooms, is located on a mesa top near the middle of Chaco Canyon, and is 0.6 miles (1.0 km) from Pueblo Bonito; it was begun between AD 1020 and 1050 during a wider building boom throughout the canyon. Its location made the community visible to most of the inhabitants of the San Juan Basin; indeed, it was only 2.3 miles (3.7 km) north of Tsin Kletsin, on the opposite side of the canyon. The community was the center of a bead- and turquoise-processing industry that influenced the development of all villages in the canyon; chert tool production was also common. Research conducted by archaeologist Tom Windes at the site suggests that only a handful of families, perhaps as few as five to twenty, actually lived in the complex; this may imply that Pueblo Alto served a primarily non-residential role.[49] Another Great House, Nuevo Alto, was built on the north mesa near Pueblo Alto; it was founded in the late 12th century, a time when the Chacoan population was declining in the canyon.

Outliers

In Chaco Canyon's northern reaches lies another cluster of Great Houses; among the largest are Casa Chiquita ("Small House"), a village built in the AD 1080s, when, in a period of ample rainfall, Chacoan culture was expanding. Its layout featured a smaller, squarer profile; it also lacked the open plazas and separate kivas of its predecessors.[50] Larger, squarer blocks of stone were used in the masonry; kivas were designed in the northern Mesa Verdean tradition. Two miles down the canyon is Peñasco Blanco ("White Bluff"), an arc-shaped compound built atop the canyon's southern rim in five distinct stages between AD 900 and 1125. A cliff painting (the "Supernova Platograph") nearby may record the sighting of the SN 1054 supernova on July 5, 1054.β[›][51]

Hungo Pavi, located 1 mi (1.6 km) from Una Vida, measured 872 feet (266 m) in circumference. Initial probes revealed 72 ground-level rooms,[52] with structures reaching four stories in height; one large circular kiva has been identified. Kin Nahasbas, built in either the 9th or 10th century, is sited slightly north of Una Vida, positioned at the foot of the north mesa. Limited excavation of it has taken place.[53]

Tsin Kletzin ("Charcoal Place"), a compound located on the Chacra Mesa and positioned above Casa Rinconada, is 2.3 miles (3.7 km) due south of Pueblo Alto, on the opposite side of the canyon. Nearby is Weritos Dam, a massive earthen structure that scientists believe provided Tsin Kletzin with all of its domestic water. The dam worked by retaining stormwater runoff in a reservoir. Massive amounts of silt accumulated during flash floods would have forced the residents to regularly rebuild the dam and dredge the catchment area.[54]

Deeper in the canyon, Una Vida ("One Life") is one of the three oldest Great Houses; construction began around AD 900. Comprising at least two stories and 124 rooms,[52] it shares an arc or D-shaped design with its contemporaries, Peñasco Blanco and Pueblo Bonito, but has a unique "dog leg" addition made necessary by topography. It is located in one of the canyon's major side drainages, near Gallo Wash, and was massively expanded after 930.[44] Wijiji ("Greasewood"), comprising just over 100 rooms, is the smallest of the Great Houses. Built between AD 1110 and 1115,[55] it was the last Chacoan Great House to be constructed. Somewhat isolated within the narrow wash, it is positioned 1 mi (1.6 km) from neighboring Una Vida.

Directly north are communities even more remote: Salmon Ruins and Aztec Ruins, sited on the San Juan and Animas Rivers near Farmington, were built during a 30-year wet period commencing in AD 1100.[6][56] Sixty miles (100 km) directly south of Chaco Canyon, on the Great South Road, lies another cluster of outlying communities. The largest, Kin Nizhoni, stands atop a 7,000-foot (2,100 m) mesa surrounded by marshy bottomlands.

Ruins

Great Houses

Immense complexes known as "Great Houses" embodied worship at Chaco. As architectural forms evolved and centuries passed, the houses kept several core traits. Most apparent is their sheer bulk; complexes averaged more than 200 rooms each, and some enclosed up to 700 rooms.[5] Individual rooms were substantial in size, with higher ceilings than Anasazi works of preceding periods. They were well-planned: vast sections or wings erected were finished in a single stage, rather than in increments. Houses generally faced the south, and plaza areas were almost always girt with edifices of sealed-off rooms or high walls. Houses often stood four or five stories tall, with single-story rooms facing the plaza; room blocks were terraced to allow the tallest sections to compose the pueblo's rear edifice. Rooms were often organized into suites, with front rooms larger than rear, interior, and storage rooms or areas.

Ceremonial structures known as kivas were built in proportion to the number of rooms in a pueblo. One small kiva was built for roughly every 29 rooms. Nine complexes each hosted an oversized Great Kiva, each up to 63 feet (19 m) in diameter. T-shaped doorways and stone lintels marked all Chacoan kivas. Though simple and compound walls were often used, Great Houses were primarily constructed of core-and-veneer walls: two parallel load-bearing walls comprising dressed, flat sandstone blocks bound in clay mortar were erected. Gaps between walls were packed with rubble, forming the wall's core. Walls were then covered in a veneer of small sandstone pieces, which were pressed into a layer of binding mud.[57] These surfacing stones were often placed in distinctive patterns. The Chacoan structures altogether required the wood of 200,000 coniferous trees, mostly hauled—on foot—from mountain ranges up to 70 miles (110 km) away.[8][58][59]

Uses

The meticulously designed buildings composing the larger Chacoan complexes did not emerge until around AD 1030. The Chacoans melded pre-planned architectural designs, astronomical alignments, geometry, landscaping, and engineering into ancient urban centers of unique public architecture. Researchers have concluded that the complex may have had a relatively small residential population, with larger groups assembling only temporarily for annual ceremonies.[8] Smaller sites, apparently more residential in character, are scattered near the Great Houses in and around Chaco. The canyon itself runs along one of the lunar alignment lines, suggesting the location was originally chosen for its astronomical significance. If nothing else, this allowed alignment with several other key structures in the canyon.[5]

Around this time, the extended Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi) community experienced a population and construction boom. Throughout the 10th century, Chacoan building techniques spread from the canyon to neighboring regions.[60] By AD 1115, at least 70 outlying pueblos of Chacoan provenance had been built within the 25,000 square miles (65,000 km2) composing the San Juan Basin. Experts speculate the function of these compounds, some large enough to be considered Great Houses in their own right. Some suggest they may have been more than agricultural communities, perhaps functioning as trading posts or ceremonial sites.[61]

Thirty such outliers spread across 65,000 square miles (170,000 km2) are connected to the central canyon and to one another by an enigmatic web of six Chacoan road systems. Extending up to 60 miles (97 km) in generally straight routes, they appear to have been extensively surveyed and engineered.[62][63] Their depressed and scraped caliche beds reach 30 feet (9.1 m) wide; earthen berms or rocks, at times composing low walls, delimit their edges. When necessary, the roads deploy steep stone stairways and rock ramps to surmount cliffs and other obstacles.[64] Though their purpose may never be certain, archaeologist Harold Gladwin noted that nearby Navajo believe that the Anasazi had built the roads to transport timber; archaeologist Neil Judd offered a similar hypothesis.[3]

See also

- Archaeoastronomical sites by country

Notes

- ^ α: The question of how to date Chacoan ruins was tackled by A. E. Douglass, the earliest practitioner of dendrochronology; consequently, the developmental chronology of Chaco Canyon's ruins is now the world's most extensively researched and accurate.[65]

- ^ β: The Crab Nebula, now a supernova remnant in the constellation of Taurus, was the result of the event in question; the original supernova attained peak brilliance on the date that the Chacoans presumably sighted it.[51]

Citations

- ↑ National Park Service 1966

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Strutin 1994, p. 6

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Fagan 2005, p. 35

- ↑ Fagan 1998, pp. 177–182

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Sofaer 1997

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Fagan 2005, p. 198

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 National Park Service 2007

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Sofaer 1999

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 5

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 43

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Hopkins 2002, p. 240

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Fagan 2005, p. 47

- ↑ Fagan 2005, pp. 46–47

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 44

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Fagan 2005, p. 45

- ↑ Frazier 2005, p. 181

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 222

- ↑ Fagan 1998, p. 177

- ↑ Stuart 2000, pp. 14–17

- ↑ Stuart 2000, p. 43

- ↑ Fagan 2005, pp. 18–19

- ↑ Noble 1991, p. 120

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 20

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 126

- ↑ Fagan 2005, pp. 55–57

- ↑ Diamond 2005, pp. 136–156

- ↑ Noble 1984, p. 11

- ↑ Noble 1984, pp. 57–58

- ↑ English 2001

- ↑ LeBlanc 1999, p. 166

- ↑ LeBlanc 1999, p. 180

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Strutin 1994, p. 57

- ↑ Strutin 1994, p. 60

- ↑ Strutin 1994, pp. 57–59

- ↑ Brugge, Hayes & Judge 1988, p. 4

- ↑ Strutin 1994, pp. 12–17

- ↑ Brugge, Hayes & Judge 1988, p. 7

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 32

- ↑ Strutin 1994, pp. 18–19

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 165

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 33

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Elliott 1995

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Strutin 1994, pp. 32

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Fagan 2005, p. 6

- ↑ National Park Service 2005

- ↑ Frazier 2005, pp. 120–121

- ↑ Strutin 1994, p. 26

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 11

- ↑ Fagan 2005, pp. 10–11

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 21

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Kelley & Milone 2004, p. 413

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Fagan 2005, p. 26

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 98

- ↑ Frazier 2005, p. 101

- ↑ Fagan 2005, pp. 6–7

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 208

- ↑ Fagan 2005, pp. 119–121

- ↑ Reynolds, Betancourt & Quade 2005, p. 1062

- ↑ Reynolds, Betancourt & Quade 2005, p. 1073

- ↑ Fagan 2005, p. 204

- ↑ Fagan 2005, pp. 202–208

- ↑ Fagan 1998, p. 178

- ↑ Noble 1984, pp. 52–53

- ↑ Strutin 1994, p. 35

- ↑ Fagan 2005, pp. 50–55

References

- Brugge, D.; Hayes, A.; Judge, W. (1988), Archeological Surveys of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, University of New Mexico Press, ISBN 0-82631-029-X

- Diamond, J. (2005), Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, Viking, ISBN 0-670-03337-5

- Elliott, M. (1995), Great Excavations, School of American Research Press, ISBN 093345242X

- English, N. B.; Betancourt, J.; Dean et al., J. S.; Quade, J (2001), "Strontium isotopes reveal distant sources of architectural timber in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 58 (21): 11891–96, doi:10.1073/pnas.211305498, PMID 11572943

- Fagan, B. (2005), Chaco Canyon: Archaeologists Explore the Lives of an Ancient Society, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-517043-1

- Fagan, B. (1998), From Black Land to Fifth Sun: The Science of Sacred Sites, Basic Books, ISBN 0-20-195991-7

- Frazier, K. (2005), People of Chaco: A Canyon and Its Culture, Norton, ISBN 0-393-30496-5

- Hopkins, R. L. (2002), Hiking the Southwest's Geology: Four Corners Region, Mountaineers, ISBN 0-89886-856-4

- Kelley, D. H.; Milone, E. F. (2004), Exploring Ancient Skies: An Encyclopedic Survey of Archaeoastronomy, Springer, ISBN 0-38795-310-8

- "Chaco Culture National Historical Park", National Register of Historic Places (Thoreau, NM: National Park Service), 1966, 1966-10-15, #148900, http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov/natreghome.do/, retrieved November 1, 2009

- United States World Heritage Periodic Report: Chaco Culture National Historical Park (Section II), National Park Service, 2005, http://www.nps.gov/oia/topics/CHCU.pdf, retrieved November 23, 2009

- Chaco Culture National Historical Park, National Park Service, 2007, http://www.nps.gov/chcu/, retrieved November 23, 2009

- Noble, D. (1984), New Light on Chaco Canyon, School of American Research Press, ISBN 0-933452-10-1

- Noble, D. (1991), Ancient Ruins of the Southwest: An Archaeological Guide, Northland, ISBN 0-87358-530-5

- Reynolds, A.; Betancourt, J.; Quade, J. et al.; Jonathan Patchett, P.; Dean, Jeffrey S.; Stein, John (2005), "87Sr/86Sr sourcing of ponderosa pine used in Anasazi Great House construction at Chaco Canyon, New Mexico", Journal of Archaeological Science 32: 1061–75, doi:10.1016/j.jas.2005.01.016, http://wwwpaztcn.wr.usgs.gov/julio_pdf/Reynolds_ea.pdf, retrieved August 21, 2009

- Sofaer, A. (1997), The Primary Architecture of the Chacoan Culture: A Cosmological Expression, University of New Mexico Press, http://www.solsticeproject.org/primarch.htm, retrieved August 21, 2009

- Sofaer, A. (1999), The Mystery of Chaco Canyon, South Carolina Educational Television

- Stuart, D. (2000), Anasazi America, University of New Mexico Press, ISBN 0-826321-79-8

- Strutin, M. (1994), Chaco: A Cultural Legacy, Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, ISBN 1-877856-45-2

Further reading

- LeBlanc, S. A. (1999), Prehistoric Warfare in the American Southwest, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, ISBN 0-87480-581-3

- Plog, S. (1998), Ancient Peoples of the American Southwest, Thames and London, ISBN 0-500-27939-X

External links

- Official

- Bill Hallett, "Chaco Culture National Historical Park", National Park Service (Look and See Publications), ISBN 1877827002, http://www.nps.gov/chcu/index.htm

- Academic

- "Chaco Digital Initiative", University of Virginia, http://www.chacoarchive.org/

- Imagery

Media related to Chaco Culture National Historical Park at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chaco Culture National Historical Park at Wikimedia Commons

- Travel

- Chaco Culture National Historical Park travel guide from Wikitravel

- Bill Hallett, "Chaco Culture National Historical Park", A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary: American Southwest (National Park Service), ISBN 1877827002, http://www.nps.gov/history/nr/travel/amsw/sw28.htm

- Other

- "Ancient Observatories: Chaco Canyon", Exploratorium, http://www.exploratorium.edu/chaco/

- Stephen Allten Brown. (2006), "The Mystery of Chaco Canyon", Solstice Project (Hodgenville, KY: Singing Rock Publications), ISBN 0977315827, http://www.solsticeproject.org/

- "Chaco Canyon National Historical Park", Traditions of the Sun (University of California), http://www.traditionsofthesun.org/viewerChaco/

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||